- Home

- Michelle Tea

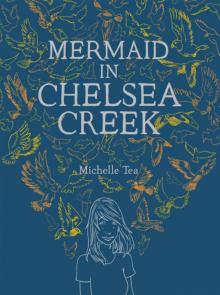

Mermaid in Chelsea Creek

Mermaid in Chelsea Creek Read online

MERMAID

IN

CHELSEA

CREEK

www.mcsweeneys.net

Copyright © 2013 Michelle Tea

Cover and interior illustrations by Jason Polan.

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part, in any form.

The McSweeney’s McMullens will publish great new books—and new editions of out-of-print classics—for individuals and families of all kinds.

McSweeney’s is a privately held company with wildly fluctuating resources.

McSweeney’s McMullens and colophon are copyright © 2012 McSweeney’s & McMullens.

ISBN: 978-1-938073-82-3

First printing 2013

MERMAID

IN

CHELSEA

CREEK

Michelle Tea

For Dashiell

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

About the Author

Prologue

Chelsea was a city where people landed. People from other countries, people running from wars and poverty, stealing away on boats that cut through the ocean into a whole new world, or on planes, relief shaking their bodies as they rattled into the sky. People had been coming to Chelsea since before Sophie Swankowski was born, since before her mother was born. Sophie’s family came from a tiny village in Poland that nobody had ever heard of and that nobody knows of still. When they came to Chelsea, a city with trolley cars and brick houses and grand trees, they brought with them smoked sausages and doughy pierogi stuffed with soft cheese, flowered scarves for the women’s heads and necklaces made from cloth and marbles. They brought with them strong magic, the magic special to their Polish village, just as all the other immigrants brought with them the magic of their abandoned lands—Russian magic and French magic, Irish magic and Puerto Rican magic, Dominican magic and Cambodian magic, Vietnamese magic, Bosnian magic, Cuban magic, up and up through the years, always a new people spilling into the small city, always with a new magic. The fading magic was carried in the bones of the grandmothers and the great-great-aunts, the old, strange women with the funny smells that scared the children born new into Chelsea, women who ate foods that worried those children, unusual foods they didn’t sell at the supermarket, where they sold everything, all of it lined up in bright boxes. The old women ate food that made their breath smell like a long-ago time, and the children were afraid of what was back there, as they scuttled out from the smothering hugs, out to the brick and cement, the telephone poles and electrical wires, the roaring buses and the graffitied everything, busted playgrounds, a city with so much wear and tear on it, so many people with so little money coming to it for so long, the threadbare buildings and dollar stores, the railroad tracks where men slept in the tall grass, the sub shops and pizza places and the corner stores selling scratchers and cigarettes, the corner bars with no windows and men inside heaped and immobile as the cracked stools they sat upon. The children ran out into the streets and the old women thought quietly about how a place could have no magic, how their grandchildren would grow up magicless and never even know it. And the old women would shed a tear and lament the old countries they’d abandoned, longing for a land where the magic came up into their bones just from standing on its earth.

* * *

ALL OF THE magics were different, but then all of them were exactly the same. And the stories brought from the many places were all different, but then, they were all the same. And the oldest story, the silliest and most dangerous story, the saddest and most hopeful story, was the story of the girl who would bring the magic, the girl who would come to save them all.

“Save us from what?” snapped the adult children, impatient with these old women and the hocus-pocus they’d never been able to shake, even with their electricity and televisions, their blenders and flushing toilets and the million plastic gadgets they could never have imagined in their village. And the old women told them about how a girl would come and she would be a magic girl, she would twist the world we think we know and knot it into a bow, she would stop time and peer into your heart, she would take on your troubles—and yours, and yours—and they would pass through her and into the earth. The old women told them about how the girl would eat salt to stay pure and unharmed, to keep her magic sharp and crystal, and about how you would know the girl as a baby who craved salt, who ate it like sugar, enough to poison a normal child to death.

The magicless adults who had been born into this new land, into Chelsea, felt sad for the old women, who had sacrificed so much to come to this new land and seemed so disappointed in it that all they could do was make up fairy tales to comfort themselves. And the old women began to die away as old women do, their aged and magic bones buried in new earth, and no one remained to tell their stories but their stories somehow remained, a low whisper that blew off the dirty harbor, that echoed with your footsteps as you passed quickly beneath an overpass, that drifted like an aroma from a kitchen window, something familiar but strange, gone before you could grasp it. They were present at slumber parties, when girls gathered like witches at midnight, the room dark and vibrating with giddy excitement and mysterious thrill, when ghosts were talked of and pranks were played, the stories crackled in the air like static electricity, passing between the girls like sparks from fingertips: a story of a girl who could let all the sadness of the world pass right through her, and everyone would be happier for it, depressions would lift and cruelties would fade and broken people would be healed by this girl who ate salt—just stupid salt, the stuff on the kitchen table. But the old women had known that salt was a crystal, made by the earth itself, full of deep magic. Salt made everything pure, and the girl who would come and swallow the world’s troubles, bringing back a golden time, would eat great piles of salt, common table salt and magical salt from the bottom of the ocean, salt pulled from the waters of the sea and salt dug out from mines and caves.

And all across the city, that city and so many cities just like it, all around the earth, there was a sense of waiting, of biding time—though if you asked them, anyone, what they thought they were waiting for, nobody would know what you were talking about.

Chapter 1

A mermaid in the creek. Through the haze of grease that formed a scum on the water, iridescent where the sun skimmed the surface, Sophie saw its body—unreal, but unmistakable. Breasts naked under the muck, hair swirling wet and weighty around her—and, yes, a tail, scaled like a fish. The mermaid had pale, stringy bits dangling from that great, muscular tail, and as she kicked beneath the waters Sophie could see the scales shift and the scabby tendrils drifting like the fringe of a jellyfish. The mermaid was graceful in her design but ragged in her condition, and as she tumbled below the waters, arcing above a shopping cart that had been left for decades to rust, her eyes searched the land above and her gaze met Sophie’s with a force that filled the girl with powerful anger and sadness. The shock woke her from her vision with a terrible jolt. All in all, Sophie had been passed out for forty-five seconds, but the dream state had the illusion of lasting much longer.

Coming to on the stiff, dirty weeds that lined the bank of the creek, Sophie could

feel her body humming. It buzzed with the gentle buzz that accompanied the pass-out game, but the pleasantness of it was sickened a bit by the bolt of dark feelings that had cut her phantasm off so abruptly. She felt it roiling in her guts like that time she’d eaten a bad slice of pizza downtown, how it had made her sweat and retch as if the pizza had become a wild beast, fighting its way back out of her. Suddenly, Sophie craved salt. In the dry cave of her mouth, down her throat, which felt strange and thick, into her tumbling tummy, she craved a bag of pretzels, the rocky salt collected at the bottom, tipped straight back into her mouth— the reward, she thought, for polishing off the snack. She longed for the greasy Tupperware salt shaker in its place on the stove, dumped onto her tongue, a wet pile she could suck on like a candy, slowly dissolving. Without thought, just animal instinct, Sophie rolled onto her side, her nose angling toward a dense tang in the air, the oceany salt of the dirty creek. Faster than her best friend could cry out in disgust, Sophie tugged her still-shimmering body to the edge of the water and plunged her face into it, mouth open, inhaling the dirty creek into her, the perfect, necessary salt of it obliterating the darker flavors of things she’d rather not think about. The sharpest taste, salt; she felt it travel through her like a delicious knife, the shock of it cutting through her, making her want more more more. She sucked at the creek hungrily, like a wild animal digging into its kill; beneath her, along the sandy, littered floor, something tumbled forward, dark and fluid.

Behind her, Ella screamed, startling a flock of pigeons into the sky.

Sophie felt a hand grip her long and tangled hair, jerking her out from the muck. Something hot grazed her cheek, singeing it: Ella’s cigarette. Sophie swatted at the burn with her creek-wet hands, unconsciously slurping at the water that sluiced from her soaked bangs into her salt-thirsty mouth. More.

“Ow!” she snapped, her face a chaos of wet, slurping and swatting and swearing. “You burned me with your cigarette!”

Ella looked briefly at the smoldering butt between her fingers, and threw it into the creek with a hot fizz. “That,” she said, “is probably the least gross thing that has ever been thrown in that creek. Do you know what’s in there? Piss! Puke! Like, rusting, germy bacteria—there are probably whole new diseases in there that you just drank. There are dead animals in there. People drown cats in there. Dogs come here to die. My uncle gets paid to dump shit in here your grandmother won’t allow at the dump. That’s toxic waste. Are you trying to die?” Unable to adequately express her rage, Ella kicked her sneaker into the earth, sending an empty soda can pinging off Sophie’s knee. Sophie stared at her friend.

“Seriously. What. The fuck. Was that.”

Sophie thought about it. As she thought, a taste arranged itself on her tongue. The luscious bite of the brine gone, she tasted—well, tastes she’d never tasted before, and probably wasn’t supposed to taste in the first place. Like sucking on the spoke of a rusty wheel, or the gelatinous plastic of a bag of drowned kittens. Grit crunched beneath her teeth, releasing a chemical that made her gums back away from her teeth. She spit away a shard of glass that had cut into the roof of her mouth, startling at the phlegmy blood that spattered on the dead grass. Ella shrieked and lit a brand new cigarette. For the first time ever, Sophie wished that she smoked. Even that burnt stink would be better than this. She thought of the times her mother had waved a hand across her face, saying Brush your teeth, it smells like something died in your mouth— well, now something had, a whole bunch of terrible something.

“Was that a cry for help? Are you, like, suicidal or fake-suicidal or however that works and you want me to, like, notice and tell your mother?” Ella released a balloon of pungent smoke into the air and Sophie tried not to gasp after it, desperate. The tingle had totally left her body, the sweet feelings of the pass-out game were gone. She was gross with creek water and horrified at what she’d done.

“I… I don’t know,” Sophie stuttered. Ella pulled a wide cloth headband from her brow. Her hair, sleek and black as a clean creek at midnight, spilled across her face, stray tendrils sticking to the strawberry gloss on her lips. She threw the headband at Sophie.

“Wipe yourself off,” Ella ordered. “Then throw it in the creek. I don’t ever want to think about that headband again.” She shuddered and took a long pull from her cigarette.

“Really,” Sophie said, bunching her unkempt bangs in the cloth and wringing out the water. “I just, I was having this dream, and it was a, a mermaid, and then I needed to drink the water, I—it’s so crazy, I don’t know why I did that!” Overwhelmed, Sophie weakly flung the headband toward the water and watched it flutter soggily to the stiff, dead grass, landing beside the jelly blob of a used condom. Both girls averted their eyes.

“Well, I’ve never heard of that,” Ella said resentfully. “I’ve never heard of passing out and then getting, like, possessed.”

“I know, me neither,” Sophie agreed.

Sophie couldn’t count how many times she’d played the pass-out game with Ella, her best and only friend. They played it in their houses when no one was home—rarely at Ella’s, with her impossibly large and ever-expanding family. They played it in the public bathrooms that no one ever used at the back of the mall, locked in the handicapped stall. They played it behind the dumpsters in the mall parking lot, they played it on the railroad tracks, each girl taking a turn, the one spotting the other, watching her tip her head over, Ella’s long, perfect hair sweeping forward like a silk curtain; Sophie’s scrunched in snarls like underbrush tangled with briars and thistle. The huffing and the puffing, the head coming back, hands squeezing the sides of the throat, breath held deep in the lungs, and then… up, up and away. How their bodies would tenderly collapse, one girl catching the other, the enchanted one drifting away into a dream like a backward fairy ring, into a place where time stalled and chugged and stalled again, so that when she came to, her body ringing with tingles, it felt as though a year had passed instead of scarcely a minute.

Sophie and Ella used to do all kinds of things. Sophie, a storyteller, would create a strange and wonderful tale and Ella would draw pictures with markers and together they would make a book. At the Salvation Army in the city square they would hunt through the dingy toy bin in search of naked and unloved Barbies, talking the clerk down from a dollar to fifty cents, and bring the doll home, where they would scrub her and untangle her synthetic locks and restore her to her proper Barbie beauty. They would play board games and watch the rerun television shows of other eras—The Brady Bunch, I Love Lucy—long into the night. But lately Ella had deemed most all activities either gay or retarded, choosing instead to practice smoking in a stylish manner and playing pass-out. Sophie could feel a new energy around her friend, as if a part of her that had been shut off was plugged in and humming, emitting a forcefield. She seemed tougher, colder, both more in your face and farther away. She seemed, Sophie realized as she watched her friend watch her through the haze of smoke that hung, clotted in the humid air, like she just didn’t like her anymore. She tried to see herself through her friend’s eyes. Her grubby clothes, her bleeding mouth, the hair she couldn’t be bothered to brush. Where Ella wore smudges of color on her face, Sophie wore dirt. Shame rose in her like mercury up a thermometer, and she shook the thought away. What did she think of Ella? Ella, whose mean streak once was such a guilty pleasure, the witty way she eviscerated dumb boys and dumber teachers, mimicking her fussy aunts, lacerating any man on the street foolish enough to make a kissy-kissy noise at her—the streak had widened, become a harsh swath, and it was aiming itself right at Sophie. Sophie felt something twitch inside her, as if she could flex a magic muscle and find herself inside her friend’s thoughts, inside her heart. She felt close to Ella in a way that felt wrong, and dangerous. Crazy.

Ella flinched. “Stop looking at me like that! You are getting more and more loco, Sophie. It’s getting weird, okay? You got to get it together, ’cause I can’t handle crazy shit like this.” She shook her

head firmly, tucking her hair behind her ears.

“It cuts off oxygen to your brain, passing yourself out,” Sophie said quickly, deflecting the blame from her, her increasing strangeness, her inability to get it together, and onto the game. “It messes with the chemicals in your blood, it’s like we’re giving ourselves seizures.”

“No it’s not,” Ella said. “Nerd. Where did you hear that?”

“The internet.”

“Nerd. Were you googling ‘passing out’?”

“Yeah, basically. I mean, why do you think everything happens? It’s ’cause we’re messing with ourselves. You know there’s a girl who passed out and never came back? She’s in a coma.”

“Liar,” Ella quipped, lighting a new cigarette off the butt of the old.

“You’re chain-smoking.”

“So. You just drank the creek. If we are in a cancer race I’d say you just leaped ahead, biiiiitch.” Ella had a way of saying biiiiitch that made Sophie crack up. And Sophie had a way of cracking up that made Ella crack up. The pair had spent so much time goading one another into hysterics, much to the annoyance of the world around them, which hardly ever thought they were funny. The burst of laughter that erupted out of them was such a relief to Sophie that she reached out to grab her friend by her newly shaved leg. Like a hammer had tapped the dip in her knee, Ella kicked out defensively, sending a spray of dirt over Sophie, to stick muddily to the wetness of her t-shirt.

“Don’t touch me, okay?” Ella snapped, backing away. “You know, Sophie, don’t you touch me, I don’t know what you got now.” Ella rubbed her legs together like twin sticks seeking fire, trying to chafe away whatever contaminant she imagined Sophie had left on her.

Sophie’s laughter stopped short, and she drew her hands back, stuffed them beneath her, her butt in terry-cloth shorts pressing her palms to the dirt. There were things about having a body that were extra hard on her friend. Sophie didn’t get why it had to be that way, but that’s how it was. It was like the world was filled with microscopic particles of filth and grime that no one but Ella could see. To Ella, bacteria, the seeds of catastrophe, the seeds of disease, lurked on toilet seats, on forks and spoons, in the air that breezed across her body. She had made a certain peace about living in a world filled with contaminants, and considered it an accomplishment that she was able to brave such filthy places as the creek bed and the mall bathroom, though if not for the blissed-out promise of the pass-out game, she’d never be able to stand it. Ella imagined her skin like a length of sponge, thirsty to soak things into her. She took lots of baths and lots of showers, and was very particular about the food she ate. Sometimes she would just get it in her head that a piece of vegetable was contaminated, or start tripping out about what the animal on her plate might have eaten in life—had it eaten poison? Bugs? Had it eaten the poop of other animals? By eating it, wouldn’t Ella be eating poison and bugs and the poop of other animals? She would push her plate away, refusing to eat. No one could convince her otherwise.

Without a Net

Without a Net Black Wave

Black Wave Girl at the Bottom of the Sea

Girl at the Bottom of the Sea Valencia

Valencia How to Grow Up

How to Grow Up Rose of No Man's Land

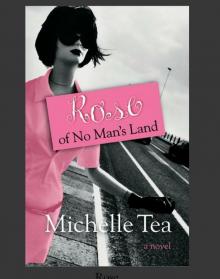

Rose of No Man's Land Mermaid in Chelsea Creek

Mermaid in Chelsea Creek